I first went to East Europe in the late eighties, a volatile time for pretty much any country in the region. I was traveling around with nothing more than a small backpack and no other interest in the world except for traveling from country to country, city to city, countryside to countryside, with a goal to learn as much about other cultures — any and every culture — as I could.

I first went to East Europe in the late eighties, a volatile time for pretty much any country in the region. I was traveling around with nothing more than a small backpack and no other interest in the world except for traveling from country to country, city to city, countryside to countryside, with a goal to learn as much about other cultures — any and every culture — as I could.

I hitched, took trains, buses and walked. My budget was some insane amount like $5 a day and I was young and stupid enough to be okay with sleeping on a park bench in a remote city if I had to. Anything went for the ‘adventure.’

Ahhh, our twenties. The time in our lives where six hour border waits, arriving in a city where there’s no or limited food, and buildings and people were equally gray didn’t phase you, it excited you.

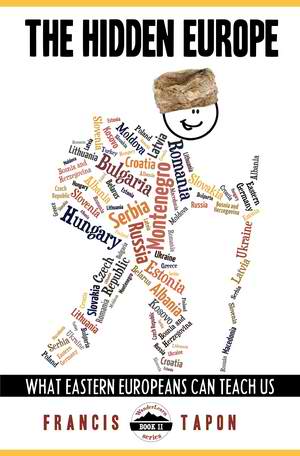

Francis Tapon, author of The Hidden Europe was not only excited by the region and all its juxtapositions, grayness and oddities in the late eighties — also his first visit — but obsessed enough to revisit a few times over a decade, most recently between 2009-2011.

It was over this three year period when he collected most of his data for the book, a combination of stats, historical references, personal adventures, escapades with locals including sexual ones, and hikes into some of Eastern Europe’s most magestic mountains.

I traveled into the very corrupt, very poor and very gray Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Russia.

A few years later, I explored a chunk of the former Yugoslavia which is now broken up into so many countries, it’s hard to keep them all straight. Areas I visited were then all one country is now Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia and…..are you dizzy yet?

What’s great about meandering into those chapters of Tapon’s book is getting a deeper understanding of why they split up, the cultural and political nuances behind independence, the implications of the war for each region and how culture came into play and affected important decisions along the way.

While the book is historical and educational, it is also witty and informal in its tone, jumping from the silly and nonsensical rules behind a country’s language and proving why stereotypes are what they are and hold more truths than not, to personal relationships he forms through couchsurfing and hitching in nearly every country.

When you meet an Eastern European (as broad as that sounds), in the west or even in their home town, they’re not the most joyous and optimistic people you’ll ever meet. Of course, there are exceptions but there often seems to be a darker side before there’s a brighter side. This doesn’t mean that they’re not interesting, smart, friendly and warm…it just means that decades under communism where your life was minimalistic and you had to live with less took its toll. The concept of “more” and an abundant life was more a fantasy than a reality.

Tapon unveils all the reasons why through anecdotes, personal interviews and thousands of years of historical trauma. Since the book is primarily targeting Americans, he often uses American-centric examples to explain the insanity of a political situation, for example, a remote and unknown pocket of Russia called Kaliningrad, which is landlocked. He references Florida in this case: “imagine if the southern part of the US became a separate country, but that Florida stayed local to the US. Floridians would be isolated. To drive to the rest of the US, Floridians would have to transit through a foreign country. Like Alaska, Kaliningrad has once again become an exclave — a disconnected piece of the mainland.”

We discover how much we can learn from Finland, a culture who loves their co-ed naked saunas and has the smartest kids in the world because of commitment to overhauling their education system. The main reason for Finland’s educational success is that teachers are highly valued and have substantial autonomy.

Estonia, which is becoming known for smart engineers where Silicon Valley is outsourcing projects to, is becoming modernized. As he notes, “Tallinn’s (the country’s capital), feels like a Hollywood set for The Lord of the Rings.” Restaurants are abundant and its language has “no sex and no future…no sex because it lacks grammatical gender (just like in English) and no future, meaning no future tense.” Another thing you might not know is that the country is known as the singing nation.

What I learned about Latvians is their diligence and perseverance. In 1989, two million demonstrators formed a human chain that spanned 600 kilometers (373 miles), and held hands for 15 minutes. It started from Tallinn, went through the capital of Latvia (Riga) and finished in the capital of Lithuania (Vilnius0) — 8 million people in those three states meaning that one in four was in that chain, one of the longest unbroken chains in history. They’re also big into mushrooming.

At the end of every country chapter, Tapon gives us a list of things we can learn from the them; some have only one or two things on the list however in the Lithuanian chapter, we learn about their importance of break and how they link many beliefs and magic with bread. In a cornerstone of a new house, Lithuanians often place a piece of bread to protect the home. While bread (and a woman’s love of flowers) are both key in Lithuanian culture, Tapon cites six things we can learn from their culture, one of the longest list in the book. A couple of countries sadly only get a couple.

The other things you learn are mysteries, such as the fact that while Belarus has a language, hardly anyone speaks it. The language is similar to Ukranian apparently but even locals don’t use it except perhaps in school. Remember Chernobyl? That’s now located in the country of Belarus and Tapon recounts his amusing and trying visit to the area, which he refers to as Radiation Land, despite the fact that the event happened over 25 years ago.

If you’re going to write a book about Eastern Europe, it wouldn’t be complete without Polish jokes and God knows we’ve all grown up with them regardless of from where we hail. I hadn’t heard of any of the jokes he recites in his book, but I’ve heard several ‘like them’ and yet, despite a century of dealing with a satirical beating, they unite when shit hits the fan and they’re loyal. While all of these things may sound like stereotypes, I have found this to be true in my dealings with Poles I met in Warsaw in the late eighties and Poles I’ve run into since in several western countries.

We dive into Prague and Budapest and the differences between them as cities and the countries as cultures. Having just revisited both places recently (my first time since my visit 20+ years ago), I resonated with most of his observations — then and now. Czech’s do consider their beer ‘holy water,’ and drink a helluva lot of it, they’re trying hard at income equality and have pride in their cities. Hungarians love to blame others for what went wrong and crikey, do they like to live in the past. Said one source he talked to, “if they’re not complaining about something, they’re either in love or depressed.” I found the same pattern when dealing with people in business during my trip to Budapest last summer.

While he brings this up continuously as a theme throughout the book for all Eastern Europeans, I found the Hungarians particularly stubbornly connected to the past, rather than focusing their efforts on the present and the future. It is true that this persistence to live in the past and blame others for their fate is a common thread in Eastern European countries. As a Brit described Slovaks, “Slovaks and English have a lot of similar traits. They can both be positively negative.” Slovakia is more agrarian than the Czech Republic and in many ways, Slovakia is like being in England 30 years ago…..”

Slovakia is also a godsend for mountain climbers and nature lovers; they’re ranked as the twelfth most environmentally conscious country in the world and the cleanest in Eastern Europe (and that’s saying a lot).

Slovenia, not to be confused with Slovakia, is one of those places very few people have heard of never mind know where it is on a map. Or if they have, they get it confused with somewhere else. When a reporter asked George W. Bush if he would make Slovakia a priority, Bush replied, “the only thing I know about Slovakia is what I learned first-hand from your foreign minister, who came to Texas.” BUT, Bush never met Slovakia’s foreign minister; he met with the Prime Minister of Slovenia. I realize we’re talking about Bush who was renowned for making diplomatic blunders, but the name is confusing, the region is confusing, the politics are confusing, and the people are confusing.

Throughout the book, there’s one story after another about people from one country living in another, speaking another language that has nothing to do with the region and not being connected to where they live. German or Russian influence where it doesn’t make sense, Ukranian influence where it might and yet, a dialect is different or culturally, they’re not aligned. One mismatch after another paints a complexity to the region that few people understand.

Speaking of misunderstood, Tapon refers to Serbia as Europe’s most misunderstood country, largely because of poor marketing on their part. Serbia lived in a bubble and underestimated our interconnectedness. It made little effort to work with the western media while Croatia and Slovenia eagerly contacted them, gave interviews and even hired American PR companies.

The funnier parts of the book is not just Tapon’s reference to getting hard-ons while encountering sultry temptresses along the way, and his references to ridiculous rules that make learning a new language or dialect insanely frustrating, but his constant reminder of how Eastern Europeans dwell in the past, are negative more often than bright despite their intelligence, and blame nearly everything on a conspiracy theory. He explains this through many historical references, a big one being the Tito myth and the dogma around his leadership.

Just after you’ve read about former communist ugliness in buildings in one city, you learn about a UNESCO World Heritage site in another, such as Mostar’s Stari Most (Old Bridge), a pedestrian-only bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He notes that the Islamic architectural influence is evident.

Just after you’ve read about former communist ugliness in buildings in one city, you learn about a UNESCO World Heritage site in another, such as Mostar’s Stari Most (Old Bridge), a pedestrian-only bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He notes that the Islamic architectural influence is evident.

“Walking over it transports you out of Europe and into another age.”

OR, how about the caves in Slovenia? From Tapon’s blog: “imagine if the Grand Canyon were underground—that should give you an idea of what to expect when you enter the Škocjanske Jame (Škocjan Caves). Lonely Planet listed them as one of the top 10 attractions in Eastern Europe. They’re also on the UNESCO World Heritage list and get 100,000 visitors a year.”

Despite the beauty in many buildings and cities, and hope in many of Balkan youth, there are many 20-something year olds who are still living in the past and more bitter than hopeful.

Said a local he met along the way about what it was like to grow up in Sarajevo when the war started, “Fuck you,” he said. “Leave our home. You can’t tell me I don’t belong here. My home,” he said his voice cracking.

As for visiting Sarajevo today, “I hate Sarajevo,” he said. It’s not my city anymore. They took it and can have it. I don’t care. I don’t give a shit about the land. Remember, honor is more important than the land.” He left him with this parting though. “Remember this, people in the Balkans may have put down their weapons, but they have not put down their anger.”

While this may have been an exceptional case where anger, hatred and pain was higher than most, it is poignant and one of the most moving exchanges in the book…at least it was for me.

We then move through Albania, the country where other Balkans think have 11.5 children, Kosovo, “the country of” Madedonia which the Greeks are apparently pissed off about, Greece whose inclusion may surprise you in a book on Eastern Europe and Turkey before we venture into two countries you’re certain should belong into: Bulgaria and Romania.

He refers to Bucharest as the poor man’s Paris and I couldn’t help but think of my trip there in the late eighties, when the city was anything but Paris. I remember reading the guidebook to the area at the time and it said something along the lines of “unless you’re into peasant culture, there’s NO reason to go to Romania.”

Despite the encouragement to avoid the place altogether, my ex and I headed there anyway — via train with nothing more than our backpacks. When we got off the train, an Italian couple (the only westerners we had seen for over two days), were approaching the track and before we had a chance to meet them, they shouted, “go back, get on the train, don’t stay. Go back….” They proceeded to share their nightmare stories: no food, limited hotels, getting ripped off, restriction after restriction and encountering unhappy people again and again.

We didn’t listen and moved forward to face our own nightmare experiences, which included angry shop and restaurant owners, packed buses that broken down on the hour, and police searches. Did I mention having a hard time finding food altogether on certain days?

Bucharest and the rest of Romania is a different experience today. (Photo on the left is the Prince Radu Vodă Monastery in Bucharest that is situated on the road that bears the same name. It belongs to the few that miraculously survived the 1980s demolition of churches).

Bucharest and the rest of Romania is a different experience today. (Photo on the left is the Prince Radu Vodă Monastery in Bucharest that is situated on the road that bears the same name. It belongs to the few that miraculously survived the 1980s demolition of churches).

While I haven’t been recently, I still have a hard time believing that Bucharest is the eastern European version of Paris when Budapest was close to

“that” for me in the late eighties under similar depressing communist conditions yet oddly isn’t close to what commercial Prague has become today. (I am basing that opinion on my trip to both cities last summer).

I only saw rural Romania by train so many years ago and Tapon was fortunate to get out into its raw beauty, which he embraced and gave a high five. He points to the fact that the country remains “fucked up” and its fucked up-ness is its paradox. Inside this paradox are stats like this one: In 2010, only nine percent of Romanians had confidence in their government, which was the lowest rate on Earth.

After finishing the chapter, I was keen to go back and add Bulgaria to the visit. I’d like to also see the new Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro since I too only saw their face from the late eighties and early nineties.

More humor abounds. Moldova’s chapter is entitled: Poor, Torn and Drunk. I had to laugh because no one deserves the drunk medal more than the Russians, which he acknowledges in the last chapter, the fat one on the country which has influenced the region the most.

Wine we need for health, and health we need to drink vodka.” — Viktor Chernomyrdin, Russia’s former Prime Minister

Poor, torn and drunk aside, he notes that one thing we can learn from Moldovans was something I resonated with. Moldovans have a tradition of picking a couple you admire to advise you and guide you through the ups and downs throughout your marriage. No one ever teaches us how its done nor is there a guidebook on relationships you get somewhere along the way in your four years of college. It’s a cool tradition and a helluva lot cheaper than a marriage counselor.

Then we get to the Ukraine, which I have a soft spot for, largely because I’ve met so many Ukranians over the years. I’m in the technology industry and it seems as if whenever something goes horribly wrong, someone will pipe up at some juncture and say, “I know a Ukranian or a Russian who can fix it.” Inevitably, they always do. Estonia comes up too but not as much as the consistent Ukranians who seem to have patches, fixes, plug-ins and workarounds for pretty much everything. It doesn’t always mean that the code is clean, but it often means your mess is fixed, at least short-term if not for longer. I also love their sarcastic sense of humor.

All that in a history of so much uncertainty. He references the country anthem which states, “The glory of Ukraine is not dead yet.” He says, “it reminds me of the Polish anthem that also has the ‘were not dead yet,’ idea. It’s as if Poland and Ukraine subconsciously knew that there will a time when greater powers of limbo, where at any moment their world can flip upside down just because their powerful neighbors sneeze.”

After you plough through each country, you start to imagine that each one becomes a character in a novel or a play where Russia is a King and one or more play Queen or Mistress for a month, ten years or a century and then become a peasant or a slave for a stint before potentially becoming a Queen or Mistress again. The complexity of the Balkans, so misunderstood and yet, so humorously and deeply unveiled in Tapon’s fascinating and engaging 721 page tale, a tale that is worth every page.

As any Balkan might say, or was that some famous Englishman at one point in time?

“I prefer the past to the present and the present to the future.” Winston Churchill

Photo credits: Photo of map, book, Slovenian caves from FrancisTapon.com site, Stari Most bridge from my.opera.com, Bucharest monastery shot: Tripomatic site.

Read some of our latest coverage on the Czech Republic, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Belarus, Kosovo, Latvia, Greece, Turkey, Lithuania, Poland, Croatia, Moldova, Finland, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, among others.

Renee Blodgett is the founder of We Blog the World. The site combines the magic of an online culture and travel magazine with a global blog network and has contributors from every continent in the world. Having lived in 10 countries and explored nearly 80, she is an avid traveler, and a lover, observer and participant in cultural diversity.

She is also the CEO and founder of Magic Sauce Media, a new media services consultancy focused on viral marketing, social media, branding, events and PR. For over 20 years, she has helped companies from 12 countries get traction in the market. Known for her global and organic approach to product and corporate launches, Renee practices what she pitches and as an active user of social media, she helps clients navigate digital waters from around the world. Renee has been blogging for over 16 years and regularly writes on her personal blog Down the Avenue, Huffington Post, BlogHer, We Blog the World and other sites. She was ranked #12 Social Media Influencer by Forbes Magazine and is listed as a new media influencer and game changer on various sites and books on the new media revolution. In 2013, she was listed as the 6th most influential woman in social media by Forbes Magazine on a Top 20 List.

Her passion for art, storytelling and photography led to the launch of Magic Sauce Photography, which is a visual extension of her writing, the result of which has led to producing six photo books: Galapagos Islands, London, South Africa, Rome, Urbanization and Ecuador.

Renee is also the co-founder of Traveling Geeks, an initiative that brings entrepreneurs, thought leaders, bloggers, creators, curators and influencers to other countries to share and learn from peers, governments, corporations, and the general public in order to educate, share, evaluate, and promote innovative technologies.